You’re reading Research Notes, a newsletter by Brendan Mattox. I read and write on topics related to fiction, memoir, and music journalism. Each issue is centered around text from my daily work, along with some notes about how it relates to what I’m doing as a whole. Please forgive any typos– I’m notoriously terrible when it comes to catching them. Today’s newsletter is a 15-20 minute read.

“The more that the secret is made into a structuring, organizing form, the thinner and more ubiquitous it becomes, the more its content becomes molecular, at the same time as its form dissolves. The secret does not as a result disappear, but it does take on a more feminine status…for women do not handle the secret in at all the same way as men (except when they reconstitute an inverted image of virile secrecy…). Men alternately fault [women] for their indiscretion, their gossiping, and for their solidarity, their betrayal. Yet it is curious how a woman can be secretive while at the same time hiding nothing, by virtue of transparency, innocence, and speed…The celerity of a war machine against the gravity of a State apparatus. Men adopt a grave attitude, knights of the secret: ‘You see what burden I bear: my seriousness, my discretion.’ But they end up telling everything— and it turns out to be nothing.”

What is a secret, and how does it work? I spent a few days over the weekend chatting with someone I met on a dating app that put me in mind of this short selection from the essay “Becoming-Intense, Becoming-Animal, Becoming-Imperceptible…” by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, printed in A Thousand Plateaus (1980), the second volume of their landmark work Capitalism and Schizophrenia. I highly recommend A Thousand Plateaus; I’ve been reading and rereading it over the course of the last year. The book is a kind of study of modernist literature, science, philosophy, etc. that creates a moving image of thought that is effective against the more rigid frameworks of society of its time, and continues to be relevant today as it was influential to many early designers and architects of web culture.

The chapter “Becoming-Intense…” may be Deleuze and Guattari’s most frustrating work. A treatment of the duo’s concept of becoming, I had a very hard time ‘getting it’ the first time around. It is one of the book’s longest essays and, as their analysis picks up speed, it feels as if the text dissolves into something more like jazz improv than a philosophy book. The section “Memories of a Secret,” quoted above, always gave me a little difficulty. A brief section of only four pages, it slides in just after a very long passage on becoming-molecular, and right before the essay as a whole jackknifes into a geometry or topology of becoming. As a result, I tended not to think about it too hard.

The woman I matched with on Bumble asked me the most interesting conversation starter I’ve gotten yet: “tell me the most toxically masculine thing you’ve ever done.” I was taken aback by it. I decided the only way to respond was to be straightforward (“in the fifth grade, I outed a friend to a group of sixth graders so that I would fit in”).

In deciding, Deleuze and Guattari’s little poke at men and their “virile secrecy” recurred to me. “Men adopt a grave attitude, knights of the secret…but they end up telling everything, and it turns out to be nothing.” Virile secrecy, according to the text, is the movement in which a secret takes on an infinite form. “We go from a [secret] content that is well-defined, localized, and belongs to the past, to the a priori general form of a non-localizable something that has happened.” The secret is rendered infinite, and along with it, an infinite guilt. All of this is related to Deleuze and, especially, Felix Guattari’s critique of psychoanalytic procedure, how under Freudian criteria the analysis of a patient becomes interminable as the subject is led over and again to rediscover the familial triangle of “Daddy-Mommy-Me” beneath the florid delirium of daily life, isolating a privileged subject from his or her material reality. “Interminable analysis: the Unconscious has been assigned the increasingly difficult task of itself being the infinite form of secrecy, instead of a simple box containing secrets. You will tell all, but in saying everything you will say nothing because all the ‘art’ of psychoanalysis is required in order to measure your contents against the pure form…When the question ‘What happened?’ attains this infinite virile form, the answer is necessarily that nothing happened, and both form and content are destroyed.’

A main project of Deleuze and Guattari, writing together, was to create an analysis of society that would be politically useful in challenging the ghosts conjured up by an increasingly diverse landscape of mediations. These representations in media, and how we’re taught to engage with them, often obstruct a free-flow of desire by channeling it towards a pre-captured formation. (“Every time desire is betrayed, cursed, uprooted from its field of immanence, a priest is behind…the most recent figure of the priest is the psychoanalyst…”) Another way of putting this is that Deleuze and Guattari are against interpretation, or at least a certain type of interpretation that begins from the idea that all desire is first of all a desire for something. It is at this point where interpretation itself departs from its immediate surroundings and takes up residence in larger structures with which desire never had any relation to begin with.

Desire desires nothing but movement; this is where Deleuze and Guattari’s most important and, maybe, obvious point comes from— all desires for an object are assembled by a series of social and technical machines that influence a desiring subject. One desires psychoanalysis, and its complex interpretations, because of the endless creative potential of interpretation— not because those interpretations necessarily point one in ‘the right direction’ (always a question, “whose direction, and why?”). My role as hermit over the last few years has lead to more than a few conversations with friends (usually about their dating lives) where interpretation has reached dizzying heights as they attempt to parse out why someone didn’t call, won’t commit, why they can’t decide, etc. At the very least, I enjoyed the conversation, though I wonder how helpful I really was.

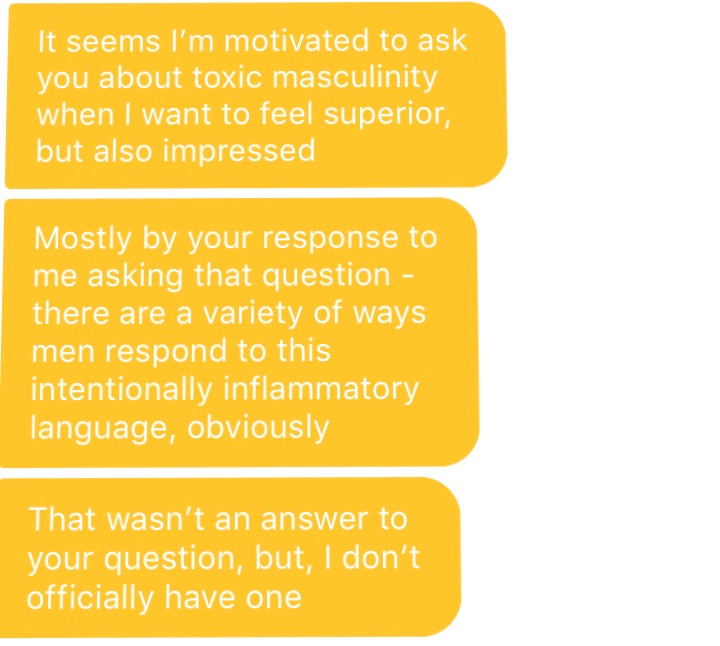

So then, Bumble…I wonder what Deleuze and Guattari would think of internet dating, particularly the absolute speed of app dating. Dating in general is a difficult process, dating on the apps even more so, dating on apps during the COVID-19 pandemic an insanity I’m sure that many of you are glad to be sitting out. The question of secrecy and transparency, always a concern in dating, feels as if it has risen to a higher degree under the circumstances of general unrest. The person I matched with this weekend had an ambiguous name (she chose a latinate phrase meaning ‘secrecy’ or perhaps her name really was Rosa and the whole thing was a highly constructed joke). She asked probing questions, but did not respond well to mine. I got the sense that I was being read, analyzed, held up against a rubric (that I am white and she was not, this is another complicating factor). “Tell me the most toxically masculine thing you’ve ever done.” How much do you respond? How is your response interpreted?

There are three stages of the secret: there is the form of the box, with its requisite content, in which something is hidden, something must be perceived (a secret is necessarily coextensive with its perception); second, there is the infinite virile secrecy, a paranoid interpretosis that seeks out guilt in every party, that is the operation of a State upon a social field, a continuous attempt to uproot spies and figure out “what’s really going on”; finally, the imperceptible secret, at the level where a secret is no longer hidden. Deleuze and Guattari’s approximation of the ‘feminine handling’ of the secret, “There are women who tell everything, sometimes in appalling, technical detail, but one knows no more at the end than at the beginning; they have hidden everything by celerity, by transparency (limpidité). They have no secret because they have become a secret themselves…This is where the secret reaches its ultimate state: its content is molecularized, at the same time as its form has been dismantled, becoming a pure moving line…”

Becoming-woman, a controversial feature of Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy, and a step on the road to becoming-secret, still felt as if it was the best option. Respond openly not because of some duty to truth, but because transparency pushes a conversation into a new register. By being transparent, I could feel just how much interpretation was being levied against me and, conversely, began to perceive a virile secrecy in my partners’ conversation. There are many good reasons to be secretive, given the world we live in— but the paranoia itself drew out of my partner an infinite delay, an interminable analysis, one that would’ve been too tiring to continue to counteract. I guess this is what it means to know something “won’t work.” We could’ve stood face-to-face and still never met in person. I unmatched.

you can read an annotated copy of “Memories of the Secret” here.

Watching, Reading, Listening…

This week, I’m reading Girlhood and the Plastic Image by Heather Warren-Crow, which is analysis of a few pieces of digital art from the turn-of-the-millennium. Warren-Crow’s most interesting idea? “Everyone on the Internet is a girl.”

Chapter 4 of Girlhood covers a few anime films from the late 90s and early 00s, including Ghost in the Shell, which I watched this week. A still relevant movie about modifying oneself as much as possible to conform to the operations of machines. It’s one of a few Japanese films I’m watching this month, including Yasujiro Ozu’s The End of the Summer (a perfect movie) and Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes.

In music, just this song, from former Yuck frontman Daniel Blumberg. Sounds like early Modest Mouse meets early Fleet Foxes.