Welcome back to Research Notes, a newsletter from Brendan Mattox. Today’s issue is a 15 minute read. Please forgive typos– I’m notoriously terrible at catching them.

Lately I’ve been interested in the growing branch of academia called platform studies, which looks into the media environments and computing beneath life on the modern web. Some recent publications in the genre that I’m excited about include The Twittering Machine, The Spotify Teardown, and the open-access (free) collection A Tumblr Book.

I recently made friends with a young woman around the same age as I am who told me about being a “Tumblr Girl” back at the beginning of the last decade, when the website existed in a brief moment of unrestrained creativity before increased control measures were introduced. Our conversation reminded me of some of my female friends from college, who were power users of the site, and then I started listening to some music I liked from back then, and this led to me falling down Kate Knibb’s “Weird Rabbit Hole of Tumblr Girls.” (2013)

“Elonie Pope, who doesn’t consider herself a Tumblr girl and runs a Tumblr Girls twitter account (which, naturally, posts pictures of Tumblr Girls) says there isn’t a strong, supportive Tumblr Girl community. “Tumblr Girls aren’t really fans of each other,” Pope explains…Pope didn’t go in-depth describing the Tumblr girl aesthetic, but she did make sure to point out that they have a homogeneous body type. “They are usually skinny.”

There was something distinctively feminine about Tumblr to me, perhaps because the site’s reliance on photo reblogging encouraged an aesthetics and fashion consciousness that guys in my sphere just did not have.

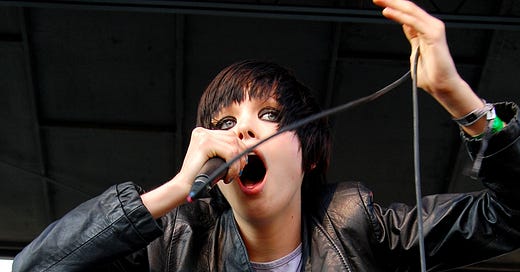

If I had to pick a public figure who defines my understanding of Tumblr, I would choose the musician and icon Alice Glass, whose style inspired a whole branch of Tumblr girl. Born Margaret Osborne, Glass was one half of the duo Crystal Castles. Writer Meaghan Garvey, in Pitchfork:

In Crystal Castles, Glass was immediately recognizable and yet completely unknowable, a shockingly visceral presence onstage but out of reach everywhere else…[Her] blunt force style transcended language barriers, and audiences from Russia to China to South Korea hung onto her every wail.

Crystal Castles was one of the great acts of the blog era, owing to the way the music could circulate regardless of whether or not you understood English. It was completely visual and auditory. Both in person and in video, Glass’ onstage antics embodied a kind of freedom that people wished they could have, a no-holds-barred approach to movement. (Even to the detriment of ones own body, barely a year went by without reports of Glass injuring herself in concert.)

Bolstering that image was the fact that, in interviews, that place where the façade of performance is presumed to fall away, Glass and her bandmate, Ethan Kath, remained inscrutable and diffident, if not outright hostile.

Again, with Meaghan Garvey:

“That whole idea is a complete illusion,” Glass tells me later on…“Since I was mysterious, you could imagine anything want, like I could be off doing so many romantic things. And I wish I was doing those things. But I wasn’t. I was just sitting around in a fucking room.”

Garvey’s interview and profile, “The Agony and Ecstasy of Alice Glass” (2018), took place after Glass revealed, in 2017, that Kath, real name Claudio Palmieri, had abused her verbally, physically, and sexually from when they met until she left Crystal Castles, a period of a decade that began when she was fifteen years-old. In a statement published to her personal website in 2017, Glass wrote:

As we started to gain attention, [Claudio] began abusively and systematically targeting and controlling my behavior: my eating habits, who I could talk to, where I could go, what I could say in public, what I was allowed to wear. He kept me from doing interviews or photoshoots unless he was in control of the situation…He became physically abusive. He held me over a staircase and threatened to throw me down it. He picked me up over his shoulders and threw me onto concrete. He took pictures of my bruises and posted them online.

This use of abusive horror as an aesthetic tool was on Crystal Castles’ palette from the start. The cover of their first extended play, Alice Practice, depicted a drawing of the pop star Madonna with a black eye.

The image kicks up a maelstrom of associations– the shock of a bruised face, the epidemic of intimate partner violence, the mediated world of celebrity– that feels very close to the history of the social web, where brutality and mediation have often gone hand-in-hand. Tangential to this is the idea that nothing circulates faster or more widely on the Internet than an image of a woman. A friend from the Boston days, one who had nebulous connections to Crystal Castles through a boyfriend in Los Angeles, once expressed that Crystal Castles was built on a similar principle: “Ethan Kath’s plan from the start was, he knew you needed to have a hot girl at the front or no one would pay attention to you.”

As I reflected on a few weeks back, Heather Warren-Crow’s Girlhood and the Plastic Image has been a nifty tool in thinking about the role that girls have played in platform culture. The object of Warren-Crow’s critique is the plasticization of girls and girlhood, which empties out the girl of subjectivity in order to make her a vessel of conveyance. The plasticity of girlhood is a myth not without its pitfalls (“borderline personality disorder,” the fickle woman, runaround Sue).

“Girlhood,” writes Warren-Crow

…is understood as a state of empty connectivity and soft, boneless flexibility…no interior, physical or psychic, at all. This is the premise of digital girlishness. Yet it is not an enabling condition for girls IRL. They are all too often instructed to embody adults’ desires without any possibility of desires of their own.

Warren-Crow’s thesis is that the social web has girled all of its users, regardless of their physical relationship to femininity. One of the key instruments in this girling, I believe, is platform culture and the way it makes use of “the slow cancellation of the future,” in which capture has descended over subjectivity, the creation of the self, by funneling it into channels which can be used to create abstract capital.

That capital is “attention,” and I’m still wanting for a very serious and complete study of the history of this concept (sound off in the comments or drop me a line if you have any leads). But one thing we can say about platform culture is that writing itself is a form of attention. Richard Seymour, in The Twittering Machine, argues that social media is the largest writing project in history; surveillance capitalism works not through a distant Big Brother who will punish us if we do something wrong, but the creation of ourselves as a subject of certain stories which can be captured by this writing project.

The Tumblr girls and the images they created of themselves out of, Knibb’s words here, “their dedication to becoming an admired digital object,” and platform cultures more generally, interest me because of their unseen presence in fiction. As a matter of character, it’s intensely tricky to think about remediated presences. A platform is an incredibly complex social and technical machine; no longer an ancillary part of social life but a new power center that needs to be disassembled.

Elsewhere…

Last week, I wrote the intro for an selected 10 of Podcast Reviews “25 Best Episodes of This American Life.” My choices were:

15. “Dawn”

339. “Break-up”

371. “Scenes from a Mall”

396. “#1 Party School”

460. “Retraction”

This American Life is an amazing show, and if you’ve never heard it, or feel like trying it again, I recommend starting with one of those, or Sarah Vowell’s “Trail of Tears” episode.

I want more